What could speak more clearly about mankind’s insecurities than the power invested in objects, from the pagan amulet to the scrap of the wood of the true cross to the lucky interview pants. Objects that carry very little value in monetary or functional terms can carry great value as symbols of something we care about, of a privately held link with our past or with an idea or person that gives them some personal significance. More than this, objects can be loved – full stop. This cannot be called a symbolic love, because it is felt as actual affection. My example is a collection of vinyl records stacked inside a cupboard for twenty years while CDs and newer technologies took over. Yes, I weeded through them and packed some for the charity shop. Then weeded through them again and offered them to friends. I watched them disappear to new homes, and if I knew the home to which they were destined I felt slightly better.

Was I going to play any of these records again? No.

Did I have some of these albums on CD? Yes, the ones I most enjoyed listening to had been replaced with CDs long ago.

Did I love these records (as different to ‘this music’)? I have to say, yes. These records had walked through life with me for a long time.

I was getting rid of them with good reason – to free up space. Rational. Sensible. I knew I would not use them again. Stifle the heartache. Goodbye, Leonard Cohen.

Maybe this was a goodbye to past feelings, or goodbye to a younger self. Yet those feelings and memories, and even the music on the albums, in my head and heart, survive the rout of the records. So maybe I simply loved the records. What does this say about human love? I hope it does not devalue the love we feel for people – that we might share out affections with objects, which, after all, don’t matter as people do. No, people should still come first if placed in a competition with objects. There might even be an argument that, when things go wrong and we make bad choices it can be when we give too much importance to objects – when we fight for possession. And alternatively, we might fight in support of ideas and find conflict between human- and idea-love. Human has to win.

I recently toured the West Bromwich Albion football ground. I’m not a fan of football and it was purely a chance offered that I took up with a vague feeling of interest. In the spanking-clean, recently built, dressing rooms (with their aromatherapy tang!), there was an old log of wood placed totem-like between the benches. We discovered it was from an oak tree that used to grow on the ground. In the past apprentices used to soften the players’ boots by dipping them in water. The boots were then thwacked against the log, which bears the marks, to give them more flexibility.

Now it stands, simply a beloved object. One can’t see it being tossed in the skip any time soon despite its present lack of function.

Of course, sports and religions gather rituals and sacred objects.

What does it mean? Perhaps it means that, despite the attachment we might have to logic and rationality in our everyday lives, there lurks in the depths attachments which are not justified on those terms. In the end, we are not going to be sensible. We will be ourselves, loaded with stuff which might, like decrepit age, be tied to us like a tin can tied to a dog’s tail, but which is singularly our own, our life’s accompaniment. Well, the edifice we build with objects is an aspect of our identity, but one we need to be careful about.

The image of the tin can is from WB Yeats:

http://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/tower#

And I doubt I’ll ever throw away my copy of his selected poems from ‘A’ level.

My latest book review:

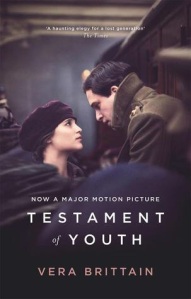

Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

‘Testament of Youth’ is a fascinating account from a well-bred English girl with a streak of rebellion at her centre. Determined to get a good education she fights tooth and nail to get into Oxford as one of the first female students in preference to settling into a middle-class country life, and after WW1 she indeed becomes one of the first women to be allowed an actual Oxford degree. High-minded and with poetic sensibilities, she falls in love with a high-achiever and has friendships with men where discussions whirl around religion and morality. As time passes and brings amazing and life-changing experiences she becomes increasingly politicised and active, but not without the pains of bereavement and disillusion which she feels belong to her generation alone. Perhaps she earns her right to be a little scathing about the following generation of young people and their jolly optimism. There is a touch of priggishness, and the blue-stocking, going on, but this is part of the charm of the testament – a testament to a lost world and lost values. I was reminded of ‘Parade’s End’ when I read this book, with its feeling of ancient values being snubbed and belittled. Vera’s experiences after the war amount, for her, to a snub of her struggles during the war and the patriotism she and her contemporaries brought to that.

A VAD during the war, Vera had to put up with all sorts of petty regulations and a lowly status. After the war, clearly exhausted and traumatised, it took time for her to start living her life again and finding purpose. I think this would be recognised now as post-traumatic stress disorder. She finds her way onward through politics, in particular through pacifism and the League of Nations, but her experiences here paradoxically show her the futility of the war fought with optimism and spirit of self-sacrifice, to which she contributed her best-loved friends and her own energies. The peace rumbles on with promises of further conflict in the punishment of the defeated. The book is highly informative about this, and shows the further disaster taking root.

Very much rooted in its time, the book moves slowly and becomes repetitive in places. There is poetry in there – it seems the best vehicle for the high-minded sentiments and for the following griefs. The language is elegant and introspective. We also hear a lot about Vera’s clothes, which is refreshing in such a serious book. VAD experiences are an eye-opener on life for the lowly nursing assistant in the stultifying hierarchy of the wards. We should read with awe for how far we’ve got (and maybe with more than a touch of gratitude).